The Bible - A Book from God?

The Bible is the central document of Christianity. Among all other scriptures it occupies a unique position. We say it is inspired. But what does that mean in concrete terms? We are far from unanimous on this question.

Divine or human?

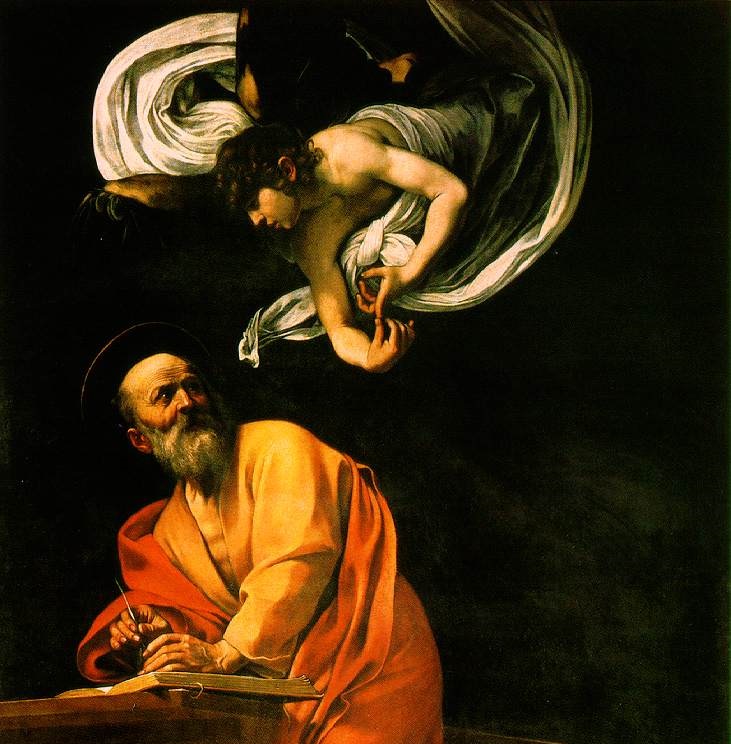

Some say that the Bible comes 100% from God. Inspiration then means for some that God has dictated Scripture word for word to the authors. I think of these medieval paintings where the Holy Spirit floats in the form of a dove next to the ear of the writer. Or, as with Caravaggio, an angel, the messenger of God, who enumerates exactly what the evangelist has to write.

Others rather emphasize the human elements of the Bible. This can go so far that they see Scripture as a 100% human book: the authors have only described their own experiences with God. And indeed, we see human signature in many places: all we have to do is compare the writing styles of the different gospels, and we recognize the very different personalities of the authors.

Every Christian with his attitude to the Bible is somewhere between these two extremes: 100% divinely “dictated” and 100% human. But our conviction about the origin of the Bible is crucial for our spiritual life and our interaction with one another. Not least because of arguments about this question Christians argue with each other and separate. There are the big camps of the “fundamentalists” and the “liberals” who differ above all by their understanding of Scripture. There is little communication, rather mutual attacks. Normally there is mostly silence between the camps.

That’s not surprising. After all, there is a lot at stake. If the Bible is the fundamental document of our faith, then it is quite a difference whether or not I ascribe to Scripture complete inerrancy. That affects my view of the world, my attitude towards science, my image of God, my self-image - and so this question shapes my life, down to the smallest detail. So is the Bible a book from God, or a human work?

Christ and Scripture: an Analogy

Peter Enns, Professor of Biblical Studies, takes an approach I find very healing. For him, it’s not about either-or, but about both-and. In “Inspiration and Incarnation”1 he writes:

[…] As Christ is both God and human, so is the Bible. In other words, we are to think of the Bible analogously to how Christians think about Jesus. Christians confess that Jesus is both God and human at the same time. He is not half God and half human. He is not sometimes one and other times the other. He is not essentially one and only apparently the other. Rather, one of the central doctrines of the Christian faith, worked out as far back as the Council of Chalcedon in AD 451, is that Jesus is 100 percent God and 100 percent human—at the same time.2

The Council thus turned against the so-called docetism. “The term docetism (Greek δοκεῖν dokein “seem”) describes the teaching that Jesus Christ only apparently had a physical body and did not feel any suffering on the cross either.”3

Enns continues:

This way of thinking of Christ is analogous to thinking about the Bible. In the same way that Jesus is—must be—both God and human, the Bible is also a divine and human book. Although Jesus was “God with us,” he still completely assumed the cultural trappings of the world in which he lived.4

Starting from the incarnation of Christ, Enns calls his approach “incarnation analogy”:

This way of thinking about the Bible is referred to differently by different theologians. The term I prefer is incarnational analogy: Christ’s incarnation is analogous to Scripture’s “incarnation.” […] My starting point is the orthodox Christian confession, however mysterious it is, that Jesus of Nazareth is the God-man. The long-standing identification between Christ the Word and Scripture the word is central to how I think through the issues raised in this book: How does Scripture’s full humanity and full divinity affect what we should expect from Scripture?5

Enns thus leaves the level of dispute, whether a statement or a story has more divine or more human aspects. For me, he thus gives Scripture back a dignity that it inevitably loses in the petty dispute. No matter on which “side” I stand.

What some ancient Christians were saying about Christ, the Docetic heresy, is similar to the mistake that other Christians have made (and continue to make) about Scripture: it comes from God, and the marks of its humanity are only apparent, to be explained away.6

“Bible Docetism”

Enns calls this “Bible docetism”.

But the human marks of the Bible are everywhere, thoroughly integrated into the nature of Scripture itself. Ignoring these marks or explaining them away takes at least as much energy as listening to them and learning from them. […]

[the Bible] belonged in the ancient worlds that produced it. It was not an abstract, otherworldly book dropped out of heaven. It was connected to and therefore spoke to those ancient cultures. The encultured qualities of the Bible, therefore, are not extra elements that we can discard to get to the real point, the timeless truths.

Rather, precisely because Christianity is a historical religion, God’s word reflects the various historical moments in which Scripture was written. God acted and spoke in history. As we learn more and more about that history, we must gladly address the implications of that history for how we view the Bible, that is, what we should expect from it.7

Of course, it is easier to take one or the other extreme position and thus close one’s eyes to the problems that arise. It always feels safer - but who says that faith has anything to do with safety? In my opinion, it is more demanding and more in keeping with the nature of the Bible to accept it as a unique work, divinely inspired, but at the same time human. And thus it cannot be free from human misunderstandings and errors.

Title picture: commons.wikimedia.org. This work is in the public domain. Retrieved: 2019-04-21

-

Eastern University, St. Davids, Pennsylvania ↩

-

Enns 2015 Enns, Peter: Inspiration and Incarnation: Evangelicals and the Problem of the Old Testament (Second Edition). Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic, an imprint of Baker Publishing Group. 2015. I quote from the eBook edition. ASIN: B00XNJGOWS. ↩

-

Enns 2015, Chapter 1 ↩

-

deacademic.com; retrieved: 2019-04-24 ↩

-

Enns 2015, Chapter 1 ↩

-

ibid. ↩

-

ibid. ↩